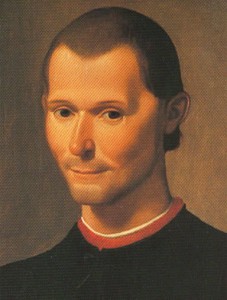

When I call Machiavelli Polybius I am alluding to the fact that there was a practice amongst the learned men of the Renaissance that each learned man adopted the name and role of an antique writer whom he resembled; While, for example, Erasmus ‘was’ Lucian, Machiavelli ‘was’ Polybius.[i]

I will now establish the central themes in Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy in so far as they are relevant to the tradition of republicanism.

I will now establish the central themes in Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy in so far as they are relevant to the tradition of republicanism.

One theme that is central to Machiavelli’s Discourses, and to pre-19th century political thought in general is the Aristotelian taxonomy of stately constitutions found in Aristotle’s Politics. (This taxonomy is to a lesser degree also Platonic, to be found in The Republic.)[ii]

Aristotle (and Machiavelli) distinguishes between three basic forms of government: The tyranny, or dictatorship, the oligarchy, or rule of the aristocracy, and the democracy, or the rule of the people.[iii] The viewpoint inherent in this taxonomy is, that either type of government could be good, but also that it could manifest itself in a corrupted version under unfortunate circumstances (e.g. a bad tyrant in a monarchical state, an obnoxious aristocracy in an ‘ottimanical’ state and so on).

What Machiavelli contributes to the discussions of this taxonomy is to introduce a certain political dynamism, or a wish for it, into his ideal of a great republic; where previous political philosophers had stressed the mixture of the best elements of oligarchy and democracy, or Medieval thinkers reconciled themselves to simply trumpeting the excellence of a solemnly monarchical state, or ‘Sacred Empire’, Machiavelli looks back on the Roman Republic and finds there what he views as a truly Mixed Government: Machiavelli introduces the last of the three forms of government, that of monarchy, into the conception of his ideal republic, which initially seems paradoxical as republics are supposed to stand in opposition to kings and tyrants.

But to Machiavelli, ‘regal power’ does not have to equal kingship and hereditary political power; instead one may find such power in public institutions, such as that of the consuls of the Roman Republic.[iv] According to Machiavelli, including ‘regal power’ in the constitution of a republic will strengthen the republic by adding adaptability and dynamism, which are sorely needed qualities in the face of an emergency.[v]

Thus we recognize one of Machiavelli’s contributions to republicanism to be his expansion and development of the doctrine of mixed government, and the introduction and elevation of political dynamism into the ideal state. These contributions were to be hugely influential to later writers, both Anglo-American and Continental.[vi] Another contribution, related to political dynamism, which we shall attribute to Machiavelli is that of the desirability of conflict which we shall now discuss.

With the possible exception of Socrates and his “Athenian Gadly”, every political thinker up until Machiavelli had traditionally held the view that cohesion and order within states was the desirable ideal. In medieval times, political philosophy naturally revered around the benefits of aristocratic/feudalistic political structures, but even in antiquity with its somewhat more mixed political landscape we find Cicero’s dictum, that nations should stick together “like bands of robbers”.

In short, we may say that Machiavelli was profoundly original in not just accepting, but also in putting himself in favour of a conflict of the orders.[vii] This terminology is derived from the historical Roman Republic with its Patrician, Equestrian, and Plebeian ‘orders’, amongst others, but the pure principle, derived of historical context could be said to be a view that stresses the diversion and de-centralization of power within the Republic as well as a valuing the dialectic between the elite/masses and the people in general.

To attain a sense of the idiosyncrasy of this view, we may note that it puts Machiavelli in direct opposition his friend and contemporary political theorist Guicciardini as well as to the Medicis. Instead these other renaissance voices tended believe that politics would be easier if only the people ‘stayed out’; i.e. exercised no political power.

In the face of this, Machiavelli stressed the contrary; importance of involving the people in the governing process: For while the people may be labile and frivolous, the people have no wish to oppress and thus the involvement of the people can be seen as a political safeguard by which to guarantee the freedom of the republic. Thus we writes:

“The feud between plebs and senate what was made this Republic [Rome] both free and mighty.”[viii]

And further:

“Those who condemn the feud between rich and poor attack the very instance that makes a state free. They see the clamour but not its beneficial effects. All legislature that serves Liberty is produced out of the conflict between the different orders of the state.”[ix]

While these observations introduce the principle of checks and balances into Republican government, to “watch and keep each other reciprocally in check”, the principle of checks and balances is actually open to the ebb and flow of political conflict (as opposed to the more static limits set fourth by the American constitution).[x] Generally, this room for a modification of the checks and balances echoed the actually leeway allowed in the historical Roman Republic, but to Machiavelli this flexibility regarding would also allow active competence (virtù) to rise to the surface of republican politics, so that the republic may align itself with fortune and prudence (Fortuna).[xi] Thus, the tenet of republican government themselves may be allowed to wax and wane over time so long as this process does not permanently debase the relationship between the orders.

Political Dynamism and the Citizen Army

Within the broader political thinking of Machiavelli, he had several reasons to pursue this goal of political dynamism through republicanism, or as he says in his own words: “A Degree of popular government [in the Republic].”

One reason Machiavelli stresses the importance of popular government would be the fact that Machiavelli, himself a military theoretician and an infantry captain, held a firm belief in schooled citizen armies as opposed to mercenaries whom he criticizes in all of his major works.[xii] As such, a republic is necessary for the establishment and proper maintenance of such a citizen army, as is of course the citizens themselves, as the military republic par excellence is of course the Roman Republic.

In a continuation of this line of reasoning, Machiavelli establishes the following argument: Since untrained soldiers cannot be relied on, and since the training and courage of mercenaries in unknown and unreliable, the army of a state must be composed of loyal subject so that it is possible to continually train the army. The best way to ensure the loyalty of the subjects is to let them partake in the government to some degree (i.e. republicanism) and – contrary to popular conception – only second best is to be in the service of a competent (possessing virtue) and feared prince.[xiii]

This partiality on behalf of the armed citizen was to be found again in both Harrington and amongst the American founding fathers. However, while the existence of armed citizens within the state might serve to guarantee the liberty of the people that would be no guarantee that the people would not abuse these liberties, given the wrong circumstances. That is why the founding fathers would later oppose the Machiavellian/Roman institution of allowing the people to exercise their will directly upon the political process by virtue of majority vote. Similarly, that is also why Machiavelli wrote, that while and armed citizen certainly possesses liberty, he does not certainly possess the political wisdom to do good and thus may all too easily vote to oppress the liberties of another, or – ultimately – vote in support of a Caesar or a Sulla, which did in fact seem to be the historical reality of the Roman past.

[i] Braudel, Fernand: A History of Civilizations p. 343

[ii] Hansen, Mogens Herman: Den moderne republikanisme og dens kritik af det liberale demokrati p. 51

[iii] Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses p. 23 See also: Hansen, Mogens Herman: Den moderne republikanisme og dens kritik af det liberale demokrati p. 54

[iv] Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses p. 29

[v] This political quality is was Bernard Crick (1970) calls adaptability, and which I refer to as dynamism. See also Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses Discourse III.9

[vi] Such as Harrington, Jefferson, Madison, Jay, Hamilton, and the Danish Ludvig Holberg to name but a few.

[vii] Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses I.4

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses I.2

[xi] Pocock, J.G.A.: The Machiavellian Moment p. 186

[xii] By ‘major works’ I mean The Prince, The Discourses and the Art of War. For the importance of citizen armies in secondary literature see Millar, Fergus: The Roman Republic in Political Thought p. 71

[xiii] Machiavelli, Niccolò: The Discourses III.31.4 See also: Millar, Fergus: The Roman Republic in Political Thought p. 71 See also The Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (1734) for an account of the military apparatus of the Roman Republic.