Test din egen personlighed i forhold til amerikanske præsidenter her (på engelsk) eller her (på dansk).

af Ryan Smith

Psykologen Dan P. McAdams er ikke så kendt i Danmark, men hans integrative teori om personlighedspsykologiens tre niveauer er nyttig for at danne sig et større perspektiv på den måde, vi anskuer personligheden på. Ifølge McAdams kan personlighedspsykologi overordnet deles op i tre niveauer.

Niveau 1 – Trækteori

Niveau 1 består ifølge McAdams af træk. Såsom hvorvidt en person er indadvendt eller udadvendt, og hvorvidt vedkommende foretrækker at forholde sig tænkende eller følende, når der skal træffes beslutninger. Niveau 1 er med andre ord de træk, som man kan tillægge en person i (tilstræbt) videnskabelige personlighedsmatricer som The Big Five-test systemet samt i Jungs typologi. Interessant nok, så anser McAdams ikke denne type information som særligt dybdegående; som han siger, så er det information, som trænede psykologer hurtigt opsnapper om andre mennesker, og ifølge McAdams er det denne type psykiske indsigter, vi falder tilbage på, når vi vil forklare ting om mennesker, som vi dybest set ikke kender godt nok til egentlig at vide noget om. McAdams er altså relativt kritisk over for trækteori og typologier, selvom han anerkender deres validitet.

Niveau 1 består ifølge McAdams af træk. Såsom hvorvidt en person er indadvendt eller udadvendt, og hvorvidt vedkommende foretrækker at forholde sig tænkende eller følende, når der skal træffes beslutninger. Niveau 1 er med andre ord de træk, som man kan tillægge en person i (tilstræbt) videnskabelige personlighedsmatricer som The Big Five-test systemet samt i Jungs typologi. Interessant nok, så anser McAdams ikke denne type information som særligt dybdegående; som han siger, så er det information, som trænede psykologer hurtigt opsnapper om andre mennesker, og ifølge McAdams er det denne type psykiske indsigter, vi falder tilbage på, når vi vil forklare ting om mennesker, som vi dybest set ikke kender godt nok til egentlig at vide noget om. McAdams er altså relativt kritisk over for trækteori og typologier, selvom han anerkender deres validitet.

Niveau 2 – Faktisk livshistorie

Niveau 2 omhandler derimod den afledte person, der opstår som en følge af de træk, vedkommende er født med, samt de betingelser, som vedkommende er født ind i. Hvad er personens mål i livet, og hvad er personens bevidste og ubevidste strategier for at opnå disse mål? En person, som er meget Følende i Jungs typologi kunne f.eks. være mere tilbøjelig til at opsøge en tilværelse som sygeplejerske eller psykolog, hvor vedkommende skal give mennesker omsorg, hvorimod en meget Tænkende type derimod kunne tænkes at blive advokat eller ingeniør, hvor de skal ”slå huller” i andre menneskers argumentation (advokat) eller måske overvejende undgå at have kontakt med andre mennesker (visse typer ingeniører). Men man kan ikke sige noget om, hvad en person har af mål i livet ud fra vedkommendes personlighedstræk alene. Man kan kun tale om større eller mindre sandsynligheder. For at blive klogere på en konkret persons mål i livet og måde at leve sit liv på, bliver man altså nødt til at bevæge sig væk fra Niveau 1 (trækteori) og videre til Niveau 2 (den specifikke persons livsforløb).

Som nævnt er McAdams kritisk over for trækteori (Niveau 1). Derfor mener McAdams, at vi som minimum bliver nødt til at bevæge os fra Niveau 1 og til Niveau 2, før vi kan sige, at vi kender en anden person. Trækteori (Niveau 1) er ifølge McAdams ikke andet end abstrakte karakteristikker. Først når det kombineres med et kendskab til personens unikke måde at udtrykke disse generelle træk på, kan vi ifølge McAdams tale om, at vi nu analyserer og kender en rigtig person af kød og blod.

Eksempelvis kunne en person, der udelukkende så mennesker gennem trækteori (Niveau 1) mene, at en person, der er meget Tænkende i Jungs typologi, var blevet advokat, fordi det ligger til Tænkende mennesker at blive advokater (undersøgelser viser, at langt de fleste advokater har en præference for Tænkning over Følen i Jungs typologi). Men hvis vi sagde, at denne person kun var blevet advokat, fordi han var Tænkende, så ville vi ifølge McAdams gå glip af de specifikke omstændigheder, der har gjort, at vedkommende oprindeligt blev advokat: Det er ikke nok at have Tænkende træk for at blive advokat; der må også være konkrete omstændigheder, der giver vedkommende adgang til at læse jura osv. Og her er McAdams’ pointe så, at vi udelukker os selv fra at opleve disse nuancer, hvis vi insisterer på kun at se personen igennem trækteori (Niveau 1).

Således kunne man sige, at Niveau 1 groft sagt består af en persons medfødte, eller tidligt formede træk, mens en persons Niveau 2 repræsenterer det liv, personen har levet op til nu, og den unikke måde, som vedkommende har udtrykt sine træk på op til nu. Niveau 1 er altså groft sagt arv (nature), mens Niveau 2 groft sagt er miljø (nurture). Men som vi nævnte i starten af denne artikel, så består McAdams model af tre niveauer. Så hvad mangler der? Jo, det tredje niveau – identitet.

Niveau 3 – Identitet og narrativ

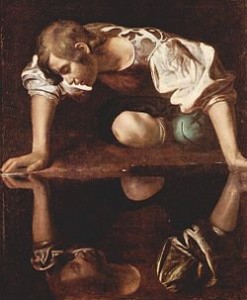

Niveau 3 omhandler ifølge McAdams en persons selvforståelse, vedkommendes personlige fortælling om sin livshistorie op til nu. Niveau 2 er det konkrete liv, som personen har levet, og Niveau 3 er den historie, som vedkommende har fortalt sig selv om sit liv op til nu. Forskellen på Niveau 2 og Niveau 3 kunne f.eks. være følgende: Lad os sige, at en person har forsøgt selvmord to gange i sit liv. Personen har måske undertrykt og fortrængt det ene forsøg, og har derfor selv en livshistorie, som indeholder et enkelt selvmordsforsøg. Men måske har personen stadig arrene på armen efter det ene selvmordsforsøg, som vedkommende altså har ”glemt” igen ved at fortrænge det. Det er præcis forskellen på Niveau 2 og Niveau 3: Niveau 2 er virkeligheden, som den ville se ud, hvis terapeuten havde et fuldstændigt indblik i patientens livshistorie. Niveau 3 er personens livshistorie, som så kan divergere mere eller mindre fra det faktiske liv (Niveau 2), men også fra vedkommendes træk (Niveau 1). En person, der er født meget indadvendt, men ser sig selv som udadvendt, er f.eks. en person, hvor vedkommendes Træk (Niveau 1) er i konflikt med vedkommendes Narrativ om sig selv (Niveau 3). Niveau 3 er altså den virkelighed, som man socialt har konstrueret for sig selv og for andre. Det er det mest overfladiske niveau, idet man kan fortælle en anden historie om sig selv end den faktiske; eksempelvis siger mange alkoholikere til sig selv, at de vitterligt ikke har noget problem med alkohol, og mange af dem tror selv på det. Men samtidig med, at Niveau 3 er det mest overfladiske niveau, så er det også det mest intense og emergente, fordi vores kommunikation med den anden altid må gå gennem personens selvforståelse (Niveau 3).

Vi kan nu vise McAdams’ model i kortform:

| McAdams-niveau | Indhold | McAdams’ mening om denne type indsigt i andre |

| Niveau 1 – Trækteori | Medfødte træk, præferencer på The Big Five, Jung-Type | Personkendskab, hvor personen kun forstås gennem abstraktioner; kendskab som var personen ”en fremmed” |

| Niveau 2 – Livsforløb og psyke | Konkret livsforløb, formative hændelser, personens mål, forsvarsmekanismer og unikke mannerismer | Umiddelbart personkendskab; mere direkte end Niveau 1, men ikke så dybt som Niveau 3 |

| Niveau 3 – Narrativitet | Personens historie om sig selv | Personkendskab, hvor man kender personen intimt |

Og her er så det skarpsindige ved McAdams’ personlighedsteori: Psykisk velvære er, ifølge McAdams, når alle tre niveauer passer sammen. Har vi f.eks. en person, som (fra naturens hånd?) er født meget indadvendt, men hvis opvækst har fundet sted i et miljø, der har påtvunget udadvendt adfærd, så passer McAdams’ Niveau 1 og 2 f.eks. ikke sammen. Der er et mismatch, som skaber følelsesmæssig ustabilitet (neuroticisme) i personen. Ligeledes, hvis personen ikke anerkender, at vedkommende har skullet “svømme mod strømmen” i sin opvækst, men fortæller sig selv, at “det da ikke var så slemt”, så passer niveau 1, 2 og 3 ikke sammen. I så tilfælde vil personen sandsynligvis have uerkendt frustration over sin opvækst, som får vedkommende til at reagere adverst i voksenlivet.

Således kan man komme på mange og varierede eksempler på, hvordan en konflikt mellem nogen af disse tre niveauer fører til uligevægtig adfærd og følelsesmæssig ustabilitet. Opskriften på psykisk sundhed er derfor: (1) Lær dine egne karakteristika at kende mht. trækteori; tag f.eks. en Jung-test, find ud af nogenlunde hvor du ligger i forhold til gennemsnittet, hvad angår personlighedstræk, opvækst, socialklasse, m.v. (2) Få afdækket evt. “løgnehistorier”, som du selv, eller din familie, kan have fortalt dig om din opvækst (f.eks. fortæller mange familier hinanden, at de er “finere” end de er, at de engang var adelige m.v.) (3) Tag et grundigt blik på dig selv og vurdér, om din nuværende livshistorie og dit nuværende selvbillede virkelig står i mål med realiteterne. På kort sigt, f.eks. til jobsamtaler eller på byture, er det måske en god idé at lyve sig bedre, end man er, men på længere sigt vil folk, der er udstyret med bare et normalt rummål af empati, kunne fornemme det, hvis man lyver for meget for sig selv, eller hvis man projicerer et selvbillede ud i omgivelserne, som ikke står i mål med virkeligheden.

Vurdering

Som det fremgår af det ovenstående, er McAdams dybest set kritisk over for trækteori, mens hans egentlige kærlighed er narrativiteten. McAdams er bedst, når han integrerer forskellige tilgange til psykologien til et større hele, og værst, når han prøver at gøre narrativitet til noget mere ”ægte” end trækteori: Selv har jeg det nemlig modsat af McAdams, og på den måde er det måske lidt ironisk, at jeg har gidet skrive om ham. McAdams mener, at vi kun virkelig kan kende en person, når vi kender vedkommende på vedkommendes egne præmisser. Jeg mener, at trækteori er det mest sigende af McAdams’ tre niveauer, og som god trækteoretiker mener jeg endvidere, at ens præference for henholdsvis trækteori eller narrativitet i sig selv kan være afledt af, hvilke træk der præger ens kognition. – Hvis jeg da ikke er enig med Buddha i, at en person dybest set ikke har noget selv, og at selvet derfor er en illusion.